Those Eyes - These EYES - THEY FADE

'Like a Dazzling Radiance'

By Nicolas Bezard

English translation. French text published in NOVO Hors série, BPM-Biennale de la Photographie de Mulhouse, 6th edition.

The exhibition “those eyes - these eyes - they fade” invites the viewer to lose themselves in a landscape of light, shadow and shadow, challenging certainties of perception in photography & revealing instead its deep connection with life.

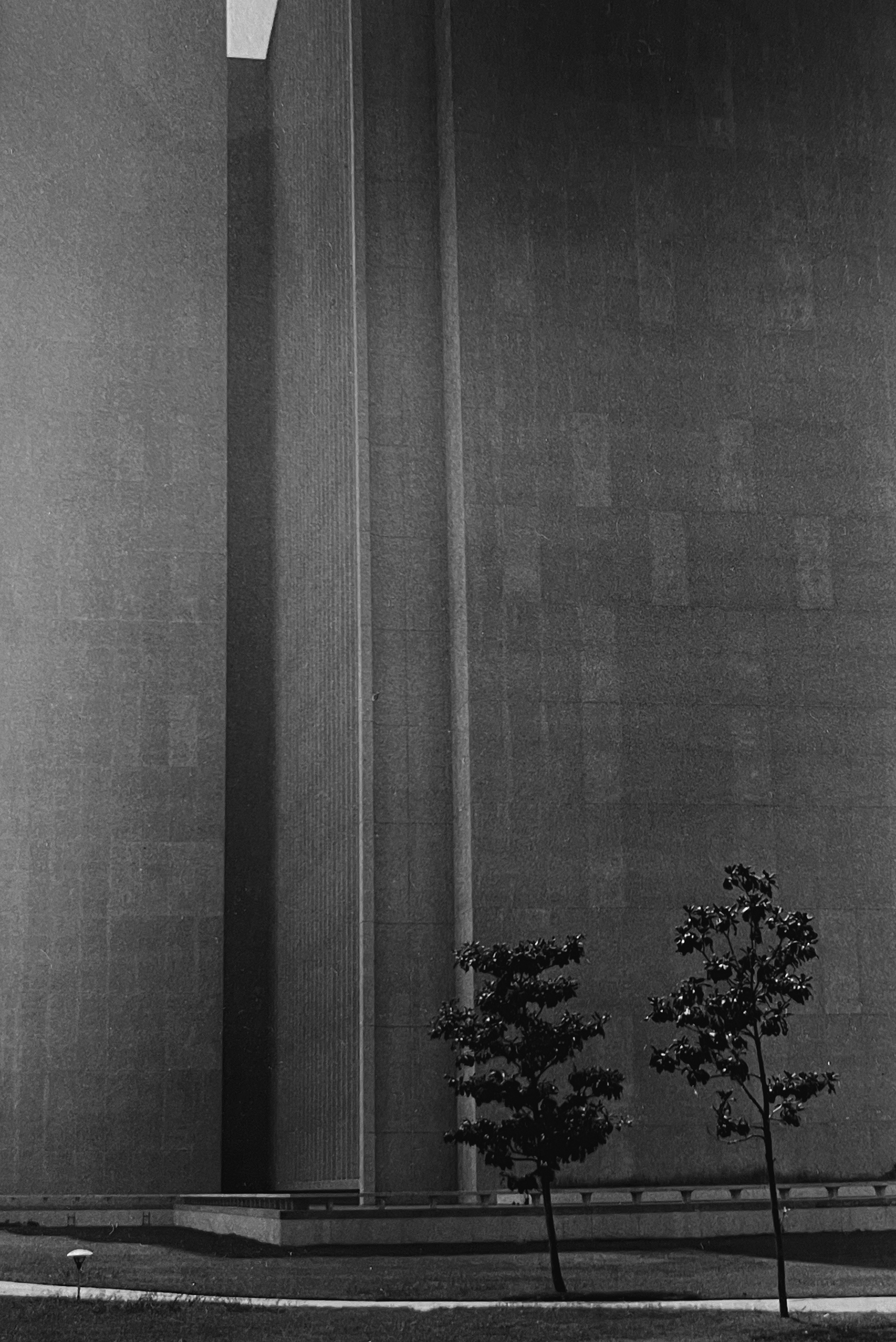

Awoiska van der Molen, #74-18

Let’s close our eyes for a moment and imagine an exhibition of photography that defies the notion that a good photo must be a sharp, clear, transparent, and objective representation of the world. The idea that a good photo must speak and show in order to say something, that it must be composed of certainties—of reality, of its own materiality.

Let’s imagine, instead, a new approach to photographic thought, where everything we see, capture, imagine, and receive is measured against a profound doubt, an original flaw in the bedrock of our understanding. From this flaw comes both our salvation and a form of modesty towards the mystery of the world that engenders, nourishes, and envelops us.

Let’s imagine that it is no longer about seeing, but about learning to see everything we miss when we look at a photographic work. No longer content with our own field of vision, we activate, in this partial eclipse of sight, other less conventional and more unsettling avenues of perception. We embrace the part of us that is dark, hidden, veiled—the primal, nocturnal underbelly of vision, where all meaningful images originate, where memories are formed.

Let’s imagine, finally, that this state of enlightened blindness is accompanied by the viewer's voluntary disorientation, a sensory drift through a space no longer arranged according to a narrative or didactic logic, but based on a prolonged movement to decompartmentalize the forms, emotions, and energies released by the works. A movement in this calm and joyful night of vision, where it would be wise to lose oneself, where every wandering would lead somewhere, where instinct would ultimately take over from reason, so that in this state of sensual and meditative wandering, we could continue to see with our eyes closed.

Now, let’s open our eyes and look forward to "those eyes - these eyes - they fade," the group exhibition conceived by Anne Immelé for the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Mulhouse. This exhibition continues the tradition of those that have, in the same venue, given each edition of the BPM its initial impetus, tone, and spirit.

Since "Les Temps Satellites" (2012), this flagship event has carried a distinctive photographic sensibility, born of the curator's personal practice—she is also a photographer—nourished by contemporary thinkers and her correspondence with other artists whose understanding of the medium resonates with her own. The artist, who in her book of the same name (published by Médiapop Éditions) questioned and highlighted photographic constellations, has patiently worked to bring other artistic worlds into the gravitational field of her affinities, rallying important figures in contemporary photography to her cause in another kind of constellation—this time, a human one.

Of course, this constellation is not static. It is a continuous movement of opening and expansion. Each time the BPM is repeated, new stars appear, enriching this community of gestures and thoughts. Among the stars who have already lit up the Mulhouse sky in the past are Bénédicte Blondeau, Raymond Meeks, and Bernard Plossu, three photographers who return in "those eyes," where their images are in dialogue with those of Nigel Baldacchino and Awoiska van der Molen.

This year's exhibition in Mulhouse is a natural, organic extension of a body of work that has evolved in other places, under different latitudes. In summer 2022, an exhibition conceived by Anne Immelé entitled "those eyes - these eyes - they fade" was held in Malta, featuring the same artists—with the exception of Raymond Meeks—but in a different configuration and with partly different works. Yet, it was already guided by the intuition of a paradoxical state in the nature of photography, capable of recording and representing the visible as well as disturbing it, questioning the associated notions of "proof" and objectivity. It explored the subterranean relationships that have connected us to living things—plants, minerals, organisms—since our origins on Earth, proposing a journey between man-made objects or structures and environments shaped or engendered by nature. In so doing, it established itself as a symbolic site for multiple passages and disturbances—from the ephemeral to the immemorial, from day to night, from the shown to the implied. It disrupted the traditional way in which viewers apprehend a photography exhibition with their bodies and senses, and the way in which photography, strictly speaking, "sees." It was a poetic invitation to set aside our presuppositions and enter an intuitive wandering between strongly marked yet porous universes, with only the compass of equivocal images to guide us—images that hover between the real and the imaginary.

The exhibition itself is a passage, for by changing its orbit and taking its place at the heart of Mondes impossibles, the conceptual anchor point initiated two years ago in Malta benefits from its installation in a new space and a revamped corpus to continue its growth, while awaiting other modes of deployment to come.

Let’s imagine, instead, a new approach to photographic thought, where everything we see, capture, imagine, and receive is measured against a profound doubt, an original flaw in the bedrock of our understanding. From this flaw comes both our salvation and a form of modesty towards the mystery of the world that engenders, nourishes, and envelops us.

Let’s imagine that it is no longer about seeing, but about learning to see everything we miss when we look at a photographic work. No longer content with our own field of vision, we activate, in this partial eclipse of sight, other less conventional and more unsettling avenues of perception. We embrace the part of us that is dark, hidden, veiled—the primal, nocturnal underbelly of vision, where all meaningful images originate, where memories are formed.

Let’s imagine, finally, that this state of enlightened blindness is accompanied by the viewer's voluntary disorientation, a sensory drift through a space no longer arranged according to a narrative or didactic logic, but based on a prolonged movement to decompartmentalize the forms, emotions, and energies released by the works. A movement in this calm and joyful night of vision, where it would be wise to lose oneself, where every wandering would lead somewhere, where instinct would ultimately take over from reason, so that in this state of sensual and meditative wandering, we could continue to see with our eyes closed.

Now, let’s open our eyes and look forward to "those eyes - these eyes - they fade," the group exhibition conceived by Anne Immelé for the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Mulhouse. This exhibition continues the tradition of those that have, in the same venue, given each edition of the BPM its initial impetus, tone, and spirit.

Since "Les Temps Satellites" (2012), this flagship event has carried a distinctive photographic sensibility, born of the curator's personal practice—she is also a photographer—nourished by contemporary thinkers and her correspondence with other artists whose understanding of the medium resonates with her own. The artist, who in her book of the same name (published by Médiapop Éditions) questioned and highlighted photographic constellations, has patiently worked to bring other artistic worlds into the gravitational field of her affinities, rallying important figures in contemporary photography to her cause in another kind of constellation—this time, a human one.

Of course, this constellation is not static. It is a continuous movement of opening and expansion. Each time the BPM is repeated, new stars appear, enriching this community of gestures and thoughts. Among the stars who have already lit up the Mulhouse sky in the past are Bénédicte Blondeau, Raymond Meeks, and Bernard Plossu, three photographers who return in "those eyes," where their images are in dialogue with those of Nigel Baldacchino and Awoiska van der Molen.

This year's exhibition in Mulhouse is a natural, organic extension of a body of work that has evolved in other places, under different latitudes. In summer 2022, an exhibition conceived by Anne Immelé entitled "those eyes - these eyes - they fade" was held in Malta, featuring the same artists—with the exception of Raymond Meeks—but in a different configuration and with partly different works. Yet, it was already guided by the intuition of a paradoxical state in the nature of photography, capable of recording and representing the visible as well as disturbing it, questioning the associated notions of "proof" and objectivity. It explored the subterranean relationships that have connected us to living things—plants, minerals, organisms—since our origins on Earth, proposing a journey between man-made objects or structures and environments shaped or engendered by nature. In so doing, it established itself as a symbolic site for multiple passages and disturbances—from the ephemeral to the immemorial, from day to night, from the shown to the implied. It disrupted the traditional way in which viewers apprehend a photography exhibition with their bodies and senses, and the way in which photography, strictly speaking, "sees." It was a poetic invitation to set aside our presuppositions and enter an intuitive wandering between strongly marked yet porous universes, with only the compass of equivocal images to guide us—images that hover between the real and the imaginary.

The exhibition itself is a passage, for by changing its orbit and taking its place at the heart of Mondes impossibles, the conceptual anchor point initiated two years ago in Malta benefits from its installation in a new space and a revamped corpus to continue its growth, while awaiting other modes of deployment to come.

Bénedicte Blondeau, Ondes, 2022-23

LIGHTS IN THE NIGHT

In Bénédicte Blondeau's silent, nebulous, amniotic images, water is made of stone and waterfalls are karstic. Forests are basaltic and abysses resemble firmaments. Spectral or boreal, clouds drift through their night, scattering life at the random whim of celestial winds. From the milky heave of foam after a wave crashes on a rock, the primordial movement of life seems to spring forth. Beneath their inert or fossilized exterior, the natural phenomena and formations photographed by the artist are imbued with a creative energy—the very energy that makes something exist rather than nothing. They seem to tell us of a succession of cataclysms. The slow, invisible work of mineral, cosmic, and organic forces that a human life, too brief and insignificant, would fail to perceive. A constant battle between life and the forces working to destroy it. A struggle of light against darkness. This supernatural light pulses and radiates beyond the translucent envelope of amoebas, revealing the contours, textures, and rough edges of an unknown world. A distant planet explored and mapped by Bénédicte Blondeau in her new series Ondes, shown for the first time in this group exhibition. A distant planet that happens to be our own.

And yet, if it takes the antediluvian and the incommensurable as its subject, it is, as the photographer explains, in the sensitive tenuity of autobiography that this project originates: "Ondes was born of a very special period in my life when two events that seemed at first sight to be poles apart—the death of my father and the gestation of my first child—occurred almost simultaneously, so that it was impossible for me not to perceive their similarities, particularly in their connection with a dimension beyond our understanding. Based on this experience, I went in search of traces of these energy waves and the alterations they left in certain landscapes: ancient glaciers, caves, or volcanic lands—whose genesis is intimately linked to the destruction of what once existed—which I then combined with visual recordings made from ultrasound, namely echograms."

Bénédicte Blondeau's unsettling images vibrate in unison with an emotion we would be hard-pressed to define. The closest we might come to it would be a kind of recognition or nostalgia, linking us to the immensity of the universe and the beginning of all life, however infinitesimal. One thing is certain: the Belgian photographer's slow, sequenced, and immersive approach to the medium enables us to experience a metaphysical vertigo in which, beyond a certain state of matter—embryonic, dilapidated, or reduced to nothingness—an energy circulates and endures. This flow of energy, which secretly underlies and conditions life, is perhaps the petroleum blue that appears in discreet touches on the surface of some of her photographs, which border on absolute black. This blue also covers the hidden area of the unknitted pages of the book, which, in the wake of the exhibition, is being published by XYZ Books. Finally, this blue, like the maternal waters of an underground river with which Ondes allows us to reconnect, holds great evocative power.

In the circularity of images and visions brought together in "those eyes, these eyes, they fade," Bénédicte Blondeau's work gently leads us towards that of Awoiska van der Molen. The latter brings together two deep black-and-white series, united by a shared fascination for the shadows and silences of the night. Urban first plunges us into a nocturnal, urban suspension of time, where, in the absence of humans, the objects, surfaces, and architectural structures that make up the city's backbone seem, in the chiaroscuro of artificial lighting, to enjoy an unsuspected beauty and poetic force. Images from The Living Mountain series shift this meditative space to lush mountain landscapes photographed only by starlight or twilight, allowing us to experience the night as an unsettling encounter with an opulent world perceived at the extreme limit of its visibility.

Like Bénédicte Blondeau, Awoiska van der Molen's artistic approach is inseparable from an existential and spiritual quest to reconnect with the living and its archaic roots. It presupposes the activation of a particular state of mind and body prior to the moment when the images are produced. In this state, where instinct takes precedence over intellect, where the artist is aware of being part of a long time, in a concentration that no distraction can break, solitude appears to be a major condition: "My images reflect what I feel when I'm outside for long periods of time in solitude," confirms the Dutch photographer. « It takes time before the noise in my head subsides. It's only after this state of physical and mental exhaustion that my perception shifts, that I reconnect with nature on a deeper level, where I can observe the landscape with fresh eyes, and where I feel less and less that I'm on the outside. Solitude thus becomes a precondition for creating works that resonate with our innermost being. Solitude makes it possible to create works that express a life force that exists in parallel with our own, independent of us, and of which we are a part. »

Words that Bénédicte Blondeau, who is also used to staging worlds in which the human figure has disappeared, would no doubt agree with. It's as if the latter have allowed themselves to be absorbed by an ever denser original darkness, except that both artists take care to provide an "escape route" in their images, whether it's a glare, isolated pulsations or a more diffuse dusting. The temptation of abstraction through monochromy thus thwarted, it's grey as a color of visual intelligence and ambiguity, expressed here in all its most subtle nuances, that finds expression.

And yet, if it takes the antediluvian and the incommensurable as its subject, it is, as the photographer explains, in the sensitive tenuity of autobiography that this project originates: "Ondes was born of a very special period in my life when two events that seemed at first sight to be poles apart—the death of my father and the gestation of my first child—occurred almost simultaneously, so that it was impossible for me not to perceive their similarities, particularly in their connection with a dimension beyond our understanding. Based on this experience, I went in search of traces of these energy waves and the alterations they left in certain landscapes: ancient glaciers, caves, or volcanic lands—whose genesis is intimately linked to the destruction of what once existed—which I then combined with visual recordings made from ultrasound, namely echograms."

Bénédicte Blondeau's unsettling images vibrate in unison with an emotion we would be hard-pressed to define. The closest we might come to it would be a kind of recognition or nostalgia, linking us to the immensity of the universe and the beginning of all life, however infinitesimal. One thing is certain: the Belgian photographer's slow, sequenced, and immersive approach to the medium enables us to experience a metaphysical vertigo in which, beyond a certain state of matter—embryonic, dilapidated, or reduced to nothingness—an energy circulates and endures. This flow of energy, which secretly underlies and conditions life, is perhaps the petroleum blue that appears in discreet touches on the surface of some of her photographs, which border on absolute black. This blue also covers the hidden area of the unknitted pages of the book, which, in the wake of the exhibition, is being published by XYZ Books. Finally, this blue, like the maternal waters of an underground river with which Ondes allows us to reconnect, holds great evocative power.

In the circularity of images and visions brought together in "those eyes, these eyes, they fade," Bénédicte Blondeau's work gently leads us towards that of Awoiska van der Molen. The latter brings together two deep black-and-white series, united by a shared fascination for the shadows and silences of the night. Urban first plunges us into a nocturnal, urban suspension of time, where, in the absence of humans, the objects, surfaces, and architectural structures that make up the city's backbone seem, in the chiaroscuro of artificial lighting, to enjoy an unsuspected beauty and poetic force. Images from The Living Mountain series shift this meditative space to lush mountain landscapes photographed only by starlight or twilight, allowing us to experience the night as an unsettling encounter with an opulent world perceived at the extreme limit of its visibility.

Like Bénédicte Blondeau, Awoiska van der Molen's artistic approach is inseparable from an existential and spiritual quest to reconnect with the living and its archaic roots. It presupposes the activation of a particular state of mind and body prior to the moment when the images are produced. In this state, where instinct takes precedence over intellect, where the artist is aware of being part of a long time, in a concentration that no distraction can break, solitude appears to be a major condition: "My images reflect what I feel when I'm outside for long periods of time in solitude," confirms the Dutch photographer. « It takes time before the noise in my head subsides. It's only after this state of physical and mental exhaustion that my perception shifts, that I reconnect with nature on a deeper level, where I can observe the landscape with fresh eyes, and where I feel less and less that I'm on the outside. Solitude thus becomes a precondition for creating works that resonate with our innermost being. Solitude makes it possible to create works that express a life force that exists in parallel with our own, independent of us, and of which we are a part. »

Words that Bénédicte Blondeau, who is also used to staging worlds in which the human figure has disappeared, would no doubt agree with. It's as if the latter have allowed themselves to be absorbed by an ever denser original darkness, except that both artists take care to provide an "escape route" in their images, whether it's a glare, isolated pulsations or a more diffuse dusting. The temptation of abstraction through monochromy thus thwarted, it's grey as a color of visual intelligence and ambiguity, expressed here in all its most subtle nuances, that finds expression.

Bernard Plossu, Los Angeles, 1974

Nigel Baldacchino, Pinetu, 2021-23

STRANGE GARDENS

It would be impossible to speak of a metaphysics of grey without evoking the work and person of Bernard Plossu, for whom grey " is the only true color of time in photography ". The room devoted to him mixes black and white images - shouldn't we just say "gray"? - taken in France and the United States in the 1970s, and more recent color photographs taken in Hyères and on the islands of Porquerolles and Port-Cros. Together, they reveal a marked contrast between two human attitudes to nature in general, and to trees and plants in particular, a plant world which, it should be remembered, precedes us by a long way in the scale of life and will outlive us just as long. The first body of black-and-white work comes from La nature prisonnière, published by Les Cahiers de l'Égaré, in which Bernard Plossu, accompanied by philosopher François Carrassan and architect Rudy Ricciotti, give us their " ecolo-visual testimony " to a key moment in the 20th century. We are at the end of the Trente Glorieuses. The photographer was travelling back and forth between France and the United States, where he had settled. From one continent to the other, he saw nature sadly falsified and pitifully parodied by zealous urban planners, who had no hesitation in planting puppet trees in the midst of free-flowing concrete to ease their conscience. " In the big cities, far from nature's havens of peace, it was obvious that man was trying to pretend that everything was fine in the best possible setting ," recalls the author of So Long, " and between the trees stuck on terraces and those planted to look 'natural', it all smacked of fakery. Following his instincts, Plossu took to the streets of Los Angeles or Paris with his 50 mm lens, denouncing this commodification of plant life, this subjugation of greenery to the modernist utopia which, from "grand ensembles" to "radiant" housing estates, soon turned into a collectivist delirium and a poorly air-conditioned nightmare.

Here, the "new city" seems to have robbed a shrub of everything, including its shade. Here, a lonely tree is wedged between a bank entrance and a parking meter, like a spurious promise of nature on credit. In another photo, small weeds, wrongly judged to be bad, " still manage to break through the solid " . How far removed we are from the Indian peoples whose aura Plossu would capture in his miniatures of the American desert! These communities lived in a spirit of humility and harmony with a nurturing nature, never suspecting that the latter would one day, like their descendants, be enslaved, parked, sacrificed on the altar of so-called progress. Bernard Plossu contrasts this concentrated vision of the park with his attachment to gardens, particularly those of the Mediterranean south of France, with which the photographer, who has lived in La Ciotat for several decades, has a long history. As a young child, he spent a year in Juan-les-Pins, in the heart of the abundant, fragrant coastal countryside. The Fresson prints on display in the exhibition, with their soft, textured colors, are like photographic reminiscences of this playful, foundational contact with flora. The images celebrate the sensuality and astonishing creativity of flora when left free to flourish on a terrace or in a garden. The garden remains one of the rare places where the two worlds - plant and human - manage to coexist peacefully, in a form of benevolent interaction. This idea of the garden was inseparable from Bernard Plossu's artistic ethic, and he took it with him wherever he went to cultivate it, even where plants were scarce - his mythical Garden of Dust series.

The work presented by photographer and architect Nigel Baldacchino is not about a garden, but a park, and more specifically the Jubilee Grove, a green space set into the urban fabric of Valletta, the capital of Malta. A special place in Maltese culture, this public park has a rich history, as the artist reminds us, based on this archipelago's central and strategic position in the Mediterranean basin: " In the 1930s, on the occasion of the Silver Jubilee, the British planted a dense grid of pine trees here, rumored to cut off insurgent gatherings near the capital. Over time, and for various reasons across the ages, this grove lent itself to becoming a space in which people could connect to a side of themselves they had to conceal elsewhere. " Thus, the discretion offered by Jubilee Grove's interlacing greenery served as a shelter for homosexual encounters, stigmatized by the island's long-dominant Catholic tradition. Today, a culture of secret male flirtation still flourishes, while at the same time the park serves as a shelter for the homeless, a meeting place for new arrivals from migratory flows, and a heroin consumption zone.

What do we see in Nigel Baldacchino's images? Not the very diverse population that the photographer knows so well, having grown up just a stone's throw from the park, but the trees, their astonishing shapes, sometimes twisted, sometimes intertwined, and which recall the sinuous trajectories of the people we meet there, " constantly breaking, healing, and on their guard ". In a sensitive, intelligent way, the photos embrace the secret, clandestine dimension of the pinewood's trees, which conceal from view more than they show. A veil of mist is sometimes added to the curtains of trees, further blurring our perception of the place and accentuating its imaginary charge. There's a deeply moving humility in Nigel Baldacchino's approach, which eschews explicit, sensationalist representation in favor of a calm, evocative approach, and chooses to assume the partial, lacunar nature of his gaze: " I like the idea of describing something and failing, like a faint flash of light on a huge object. None of the truths I've encountered have been 'complete', in a way, and that's also what poetry is for. "

Photography never challenges or moves as much as when it is the site of doubt. In keeping with the way he questions the limits of the photographic gaze, Baldacchino, who also works as an exhibition designer, plays with the materiality of his images (in a wide variety of formats) by printing them on sheets of awagami paper. He then stretches them vertically using wooden structures of his own design, drawing planes in space. Pinetu, the installation imagined for the museum's small room, invites visitors to wander between different degrees of transparency or opacity in the photographs, different levels of tension between depth and surface, symbolically recreating the bewitching, layered, multidimensional context of the Jubilee Groove.

Here, the "new city" seems to have robbed a shrub of everything, including its shade. Here, a lonely tree is wedged between a bank entrance and a parking meter, like a spurious promise of nature on credit. In another photo, small weeds, wrongly judged to be bad, " still manage to break through the solid " . How far removed we are from the Indian peoples whose aura Plossu would capture in his miniatures of the American desert! These communities lived in a spirit of humility and harmony with a nurturing nature, never suspecting that the latter would one day, like their descendants, be enslaved, parked, sacrificed on the altar of so-called progress. Bernard Plossu contrasts this concentrated vision of the park with his attachment to gardens, particularly those of the Mediterranean south of France, with which the photographer, who has lived in La Ciotat for several decades, has a long history. As a young child, he spent a year in Juan-les-Pins, in the heart of the abundant, fragrant coastal countryside. The Fresson prints on display in the exhibition, with their soft, textured colors, are like photographic reminiscences of this playful, foundational contact with flora. The images celebrate the sensuality and astonishing creativity of flora when left free to flourish on a terrace or in a garden. The garden remains one of the rare places where the two worlds - plant and human - manage to coexist peacefully, in a form of benevolent interaction. This idea of the garden was inseparable from Bernard Plossu's artistic ethic, and he took it with him wherever he went to cultivate it, even where plants were scarce - his mythical Garden of Dust series.

The work presented by photographer and architect Nigel Baldacchino is not about a garden, but a park, and more specifically the Jubilee Grove, a green space set into the urban fabric of Valletta, the capital of Malta. A special place in Maltese culture, this public park has a rich history, as the artist reminds us, based on this archipelago's central and strategic position in the Mediterranean basin: " In the 1930s, on the occasion of the Silver Jubilee, the British planted a dense grid of pine trees here, rumored to cut off insurgent gatherings near the capital. Over time, and for various reasons across the ages, this grove lent itself to becoming a space in which people could connect to a side of themselves they had to conceal elsewhere. " Thus, the discretion offered by Jubilee Grove's interlacing greenery served as a shelter for homosexual encounters, stigmatized by the island's long-dominant Catholic tradition. Today, a culture of secret male flirtation still flourishes, while at the same time the park serves as a shelter for the homeless, a meeting place for new arrivals from migratory flows, and a heroin consumption zone.

What do we see in Nigel Baldacchino's images? Not the very diverse population that the photographer knows so well, having grown up just a stone's throw from the park, but the trees, their astonishing shapes, sometimes twisted, sometimes intertwined, and which recall the sinuous trajectories of the people we meet there, " constantly breaking, healing, and on their guard ". In a sensitive, intelligent way, the photos embrace the secret, clandestine dimension of the pinewood's trees, which conceal from view more than they show. A veil of mist is sometimes added to the curtains of trees, further blurring our perception of the place and accentuating its imaginary charge. There's a deeply moving humility in Nigel Baldacchino's approach, which eschews explicit, sensationalist representation in favor of a calm, evocative approach, and chooses to assume the partial, lacunar nature of his gaze: " I like the idea of describing something and failing, like a faint flash of light on a huge object. None of the truths I've encountered have been 'complete', in a way, and that's also what poetry is for. "

Photography never challenges or moves as much as when it is the site of doubt. In keeping with the way he questions the limits of the photographic gaze, Baldacchino, who also works as an exhibition designer, plays with the materiality of his images (in a wide variety of formats) by printing them on sheets of awagami paper. He then stretches them vertically using wooden structures of his own design, drawing planes in space. Pinetu, the installation imagined for the museum's small room, invites visitors to wander between different degrees of transparency or opacity in the photographs, different levels of tension between depth and surface, symbolically recreating the bewitching, layered, multidimensional context of the Jubilee Groove.

Raymond Meeks, Erase, after nature, 2024

THAT MOMENT WHEN THE EYE OPENS

The exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts has always been a place where a certain idea of photography is cultivated, defended and clarified. "Those eyes, these eyes, they fade" is no exception to the rule, and follows on from "Sous influence" (2022), "Ce noir tout autour qui paraît nous cerner" (2020) and "Attraction(s) - L'étreinte du tourbillon" (2018), this highlight of the BPM can also be seen as an artistic manifesto highlighting the fact that photography is not limited to the production of eloquent images, but denotes a singular attitude to life, a poetic way of inhabiting the world, a sensitive ethic of the creative gesture.

To define this field of exploration, let's start by saying what it is not and what it rejects: a flashy, chatty photographic aesthetic that seeks to be edifying or has the pretension of exhaustiveness. An aesthetic intoxicated by its technicality, blind by its ambition to show us everything, to tell us everything. Obscenely literal photographs, devoid of out-of-frame or depth, that can be consumed by the blink of an eye.

Quite the opposite, in fact, to the slow-burning visual poems offered by American photographer Raymond Meeks in his never-before-exhibited series 'Erasure, After Nature', shot in the Californian desert in early 2024. In warm, soft shades of grey that glide discreetly towards color, the man we know as much for the extreme care with which he makes his own prints as for his artisanal practice of the artist's book, photographs the scraps left behind by the industrial world in the remote and, one would think, immaculate places that are the great desert plains of the American West. Showing mostly fragments of structures we ignore the original use of, debris of all kinds whose constitution we can't determine, the images evoke those cemeteries where, on most of the graves, we can no longer read any names. They are also reminiscent of the crash zones we've all seen on TV, except that on the arid mesas surveyed by Meeks, it's not aircraft that has disintegrated, but the dreams of abundance and invincibility of our ultra-productivist societies. Simple and modest in his approach - a man walks through the desert and photographs the ruins of capitalism, minimalist in its format and visual grammar reduced to the essentials - lines, dots, planes - this work touches us with its stripped-down simplicity. The artist seems to be moving directly towards abstraction, without trying, through an overbearing or didactic discourse, to show us the ins and outs of his path. He's simply there, with us, in that moment when our gaze opens up and wanders before the incongruous beauty of these few human traces scattered across the immensity of the landscape.

In his Lecture on Nothing, delivered at the Artist's Club in New York in 1949, the American composer John Cage - another great poet of subtraction - said: " Structure without life is dead. But life without structure is invisible." The strength of Raymond Meeks' vision lies in the fact that he manages, with the very basic adjustment variables of photography - frame, composition, exposure - to order the chaos of life, to give it an intelligible and poetically receivable form, to unburden it of clutter so that it can deliver something of its essence, mysterious or otherwise. As in certain paintings by Joan Miró or studies by Vassily Kandinsky - see the uncanny similarity between images from the Erasure, After Nature series and, for example, Kandinsky's Drawing for Point and Line on Plan (1925) - the combination of lines, textures and geometric volumes represented by the remains discovered and contemplated by Meeks creates a kind of musicality, as if the photographer had composed a score on the basis of these very tenuous graphic elements.

Of course, these images, which literally vibrate before our eyes and summon up the near and the far, the present and the past, can only be obtained after the photographer has immersed himself in the place whose memory he decides to question: " I'm not a prolific photographer," explains the native of Columbus, Ohio. " I don't always have a camera with me. I spend more time without one, partly because as soon as I have a camera, the thing I'm interested in escapes me - I don't see it. First I have to experience it without a camera, and then I hope that when I return to the place where it appeared, I'll be able to capture what attracted me to it the first time. I'm really slow at organizing things visually and understanding things, so I have to experience and feel these things first before I can photograph them." A delightful way of making room for slowness, contingency and even the notion of failure (those so-called "failed" photos so dear to a Bernard Plossu, and which are among the most successful of his work) in the photographic experience, just as Nigel Baldacchino, Bénédicte Blondeau and Awoiska van der Molen do when they tell us about this long, complex process that cannot be reduced to a simple blink of the eye or a press of the shutter release.

To define this field of exploration, let's start by saying what it is not and what it rejects: a flashy, chatty photographic aesthetic that seeks to be edifying or has the pretension of exhaustiveness. An aesthetic intoxicated by its technicality, blind by its ambition to show us everything, to tell us everything. Obscenely literal photographs, devoid of out-of-frame or depth, that can be consumed by the blink of an eye.

Quite the opposite, in fact, to the slow-burning visual poems offered by American photographer Raymond Meeks in his never-before-exhibited series 'Erasure, After Nature', shot in the Californian desert in early 2024. In warm, soft shades of grey that glide discreetly towards color, the man we know as much for the extreme care with which he makes his own prints as for his artisanal practice of the artist's book, photographs the scraps left behind by the industrial world in the remote and, one would think, immaculate places that are the great desert plains of the American West. Showing mostly fragments of structures we ignore the original use of, debris of all kinds whose constitution we can't determine, the images evoke those cemeteries where, on most of the graves, we can no longer read any names. They are also reminiscent of the crash zones we've all seen on TV, except that on the arid mesas surveyed by Meeks, it's not aircraft that has disintegrated, but the dreams of abundance and invincibility of our ultra-productivist societies. Simple and modest in his approach - a man walks through the desert and photographs the ruins of capitalism, minimalist in its format and visual grammar reduced to the essentials - lines, dots, planes - this work touches us with its stripped-down simplicity. The artist seems to be moving directly towards abstraction, without trying, through an overbearing or didactic discourse, to show us the ins and outs of his path. He's simply there, with us, in that moment when our gaze opens up and wanders before the incongruous beauty of these few human traces scattered across the immensity of the landscape.

In his Lecture on Nothing, delivered at the Artist's Club in New York in 1949, the American composer John Cage - another great poet of subtraction - said: " Structure without life is dead. But life without structure is invisible." The strength of Raymond Meeks' vision lies in the fact that he manages, with the very basic adjustment variables of photography - frame, composition, exposure - to order the chaos of life, to give it an intelligible and poetically receivable form, to unburden it of clutter so that it can deliver something of its essence, mysterious or otherwise. As in certain paintings by Joan Miró or studies by Vassily Kandinsky - see the uncanny similarity between images from the Erasure, After Nature series and, for example, Kandinsky's Drawing for Point and Line on Plan (1925) - the combination of lines, textures and geometric volumes represented by the remains discovered and contemplated by Meeks creates a kind of musicality, as if the photographer had composed a score on the basis of these very tenuous graphic elements.

Of course, these images, which literally vibrate before our eyes and summon up the near and the far, the present and the past, can only be obtained after the photographer has immersed himself in the place whose memory he decides to question: " I'm not a prolific photographer," explains the native of Columbus, Ohio. " I don't always have a camera with me. I spend more time without one, partly because as soon as I have a camera, the thing I'm interested in escapes me - I don't see it. First I have to experience it without a camera, and then I hope that when I return to the place where it appeared, I'll be able to capture what attracted me to it the first time. I'm really slow at organizing things visually and understanding things, so I have to experience and feel these things first before I can photograph them." A delightful way of making room for slowness, contingency and even the notion of failure (those so-called "failed" photos so dear to a Bernard Plossu, and which are among the most successful of his work) in the photographic experience, just as Nigel Baldacchino, Bénédicte Blondeau and Awoiska van der Molen do when they tell us about this long, complex process that cannot be reduced to a simple blink of the eye or a press of the shutter release.

THOSE EYES - THESE EYES - THEY FADE

Bénédicte Blondeau, Nigel Baldacchino, Bernard Plossu, Raymond Meeks, Awoiska van der Molen. //

Commissaire : Anne Immelé

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Mulhouse

13 septembre 2024 - 5 janvier 2025

Bénédicte Blondeau, Nigel Baldacchino, Bernard Plossu, Raymond Meeks, Awoiska van der Molen. //

Commissaire : Anne Immelé

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Mulhouse

13 septembre 2024 - 5 janvier 2025